6 minutes

An introduction to how JavaScript package managers work

A few days ago, ashley williams, one of the leaders of the Node.js community, tweeted this:

I didn’t really understand what she meant, so I decided to dig in deeper and read about how package managers work.

This was right when the newest kid on the JavaScript package manager block — Yarn — had just arrived and was generating a lot of buzz.

So I used this opportunity to also understand how and why Yarn does things differently from npm.

I had so much fun researching this. I wish I’d done so a long time ago. So I wrote this simple introduction to npm and Yarn to share what I’ve learned.

Let’s start with some definitions:

What is a package?

A package is a reusable piece of software which can be downloaded from a global registry into a developer’s local environment. Each package may or may not depend on other packages.

What is a Package Manager?

Simply put — a package manager is a piece of software that lets you manage the dependencies (external code written by you or someone else) that your project needs to work correctly.

Most package managers juggle the following pieces of your project:

Project Code

This is the code of your project for which you need to manage various dependencies. Typically, all of this code is checked into a version control system like Git.

Manifest file

This is a file that keeps track of all your dependencies (the packages to be managed). It also contains other metadata about your project. In the JavaScript world, this file is your [package.json](https://docs.npmjs.com/files/package.json)

Dependency code

This code constitutes your dependencies. It shouldn’t be mutated during the lifetime of your application, and should be accessible by your project code in memory when it’s needed.

Lock file

This file is written automatically by the package manager itself. It contains all the information needed to reproduce the full dependency source tree. It contains information about each of your project’s dependencies, along with their respective versions.

It’s worth pointing out at this point that Yarn uses a lockfile, while npm doesn’t. We’ll talk about the consequences of this distinction in a bit.

Now that I’ve introduced you to the parts of a package manager, let’s discuss dependencies themselves.

Flat versus Nested Dependencies

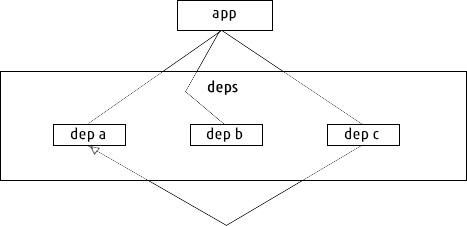

To understand the difference between the Flat versus Nested dependency schemes, let’s try visualizing a dependency graph of dependencies in your project.

It’s important to keep in mind that the dependencies your project depends on might have dependencies of their own. And these dependencies may in turn have some dependencies in common.

To make this clear, let’s say our application depends on dependencies A, B and C, and C depends on A.

Flat Dependencies

Dependency graph in case of flat dependencies

As shown in the image, both the app and C have A as their dependency. For dependency resolution in a flat dependency scheme, there is only one layer of dependencies that your package manager needs to traverse.

Long story short — you can have only one version of a particular package in your source tree, as there is one common namespace for all your dependencies.

Suppose that package A is upgraded to version 2.0. If your app is compatible with version 2.0, but package C isn’t, then we need two versions of package A in order to make our app work correctly. This is known an Dependency Hell.

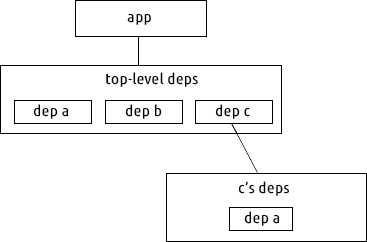

Nested Dependencies

Dependency graph in case of nested dependencies

One simple solution to deal with the problem of Dependency Hell is to have two different versions of package A — version 1.0 and version 2.0.

This is where nested dependencies come into play. In case of nested dependencies, every dependency can isolate its own dependencies from other dependencies, in a different namespace.

The package manager needs to traverse multiple levels for dependency resolution.

We can have several copies of a single dependency in such a scheme.

But as you might have guessed, this leads to a few problems too. What if we add another package — package D — and it also depends on version 1.0 of package A?

So with this scheme, we can end up with duplication of version 1.0 of package A. This can cause confusion, and takes up unnecessary disk space.

One solution to the above problem is to have two versions of package A, v1.0 and v2.0, but only one copy of v1.0 in order to avoid unnecessary duplication. This is the approach taken by npm v3, which reduces the time taken to traverse the dependency tree considerably.

As ashley williams explains, npm v2 installs dependencies in a nested manner. That’s why npm v3 is considerably faster by comparison.

Determinism vs Non-determinism

Another important concept in package managers is that of determinism. In the context of the JavaScript ecosystem, determinism means that all computers with a given package.json file will all have the exact same source tree of dependencies installed on them in their node_modules folder.

But with a non-deterministic package manager, this isn’t guaranteed. Even if you have the exact same package.json on two different computers, the layout of your node_modules may differ between them.

Determinism is desirable. It helps you avoid “worked on my machine but it broke when we deployed it” issues, which arise when you have different node_modules on different computers.

This popular developer meme illustrates the problems with non-determinism.

npm v3, by default has non-deterministic installs and offers a shrinkwrap feature to make installs deterministic. This writes all the packages on the disk to a lockfile, along with their respective versions.

Yarn offers deterministic installs because it uses a lockfile to lockdown all the dependencies recursively at the application level. So if package A depends on v1.0 of package C, and package B depends on v2.0 of package A, both of them will be written to the lockfile separately.

When you know the exact versions of the dependencies you’re working with, you can easily reproduce builds, then track down and isolate bugs.

“To make it more clear, your

package.jsonstates “what I want” for the project whereas your lockfile says “what I had” in terms of dependencies. — Dan Abramov

So now we can return to the original question that started me on this learning spree in the first place: Why is it considered a good practice to have lockfiles for applications, but not for libraries?

The main reason is that you actually deploy applications. So you need to have deterministic dependencies that lead to reproducible builds in different environments — testing, staging, and production.

But the same isn’t true for libraries. Libraries aren’t deployed. They’re used to build other libraries, or in application themselves. Libraries need to be flexible so that they can maximize compatibility.

If we had a lockfile for each dependency (library) that we used in an application, and the application was forced to respect these lockfiles, it would be impossible to get anywhere close to a flat dependency structure we talked about earlier, with the semantic versioning flexibility, which is the best case scenario for dependency resolution.

Here’s why: if your application has to recursively honor the lockfiles of all your dependencies, there would be version conflicts all over the place — even in relatively small projects. This would cause a large amount of unavoidable duplication due to semantic versioning.

This is not to say that libraries can’t have lockfiles. They certainly can. But the main takeaway is that package managers like Yarn and npm — which consume these libraries — will not respect those lockfiles.