5 minutes

Harvest, Yield, and Scalable Tolerant Systems

This post presents a summary of the paper “Harvest, Yield, and Scalable Tolerant Systems” published by Eric Brewer & Amando Fox in 1999.

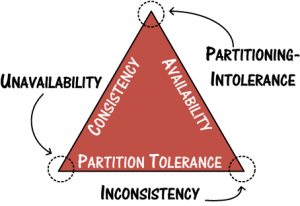

This paper deals with the trade offs between consistency and availability for large systems. It’s very easy to point to CAP and assert that no system can have consistency and availability. However, there is a catch. CAP has been misunderstood in a variety of ways. As Coda Hale explains in his excellent blog post “You Can’t Sacrifice Partition Tolerance”:

Of the CAP theorem’s Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance, Partition Tolerance is mandatory in distributed systems. You cannot not choose it. Instead of CAP, you should think about your availability in terms of yield (percent of requests answered successfully) and harvest (percent of required data actually included in the responses) and which of these two your system will sacrifice when failures happen.

This paper focuses on increasing the availability of large scale systems by fault toleration, containment & isolation.

This paper focuses on increasing the availability of large scale systems by fault toleration, containment & isolation.

We assume that clients make queries to servers, in which case there are at least two metrics for correct behavior: yield, which is the probability of completing a request, and harvest, which measures the fraction of the data reflected in the response, i.e. the completeness of the answer to the query.

The two metrics, harvest and yield can be summarized as follows:

- Harvest : data in response/total data

Example: If one of the nodes is down in a 100 node cluster, the harvest is 99% for the duration of the fault.

- Yield : requests completed with success/total number of requests

Note: Yield is different from uptime. Yield specifically deals with the number of requests, not just the time the system wasn’t able to respond to requests.

The paper argues that while there are certain systems which require perfect responses to queries every single time, there are systems that can tolerate imperfect answers once in a while. To increase the overall availability of our systems, we need to carefully think through the required consistency and availability guarantees it needs to provide.

Trading Harvest for Yield — Probabilistic Availability

Nearly all systems are probabilistic whether they realize it or not. In particular, any system that is 100% available under single faults is probabilistically available overall (since there is a non-zero probability of multiple failures)

Fox and Brewer talk about understanding the probabilistic nature of availability. This helps in understanding and limiting the impact of faults by making decisions about what needs to be available and what kind of faults can the system deal with.

They outline the linear degradation of harvest in case of multiple node faults. The harvest is directly proportional to the number of nodes that are functioning correctly, hence it’s decreases/increases linearly. Two strategies are suggested for increasing the yield:

- Random distribution of data on the nodes. If one of the nodes goes down, the average-case and worst-case fault behavior doesn’t change. Instead if the distribution isn’t random, then depending type of data, the impact of a fault maybe variable. For example, if only one of the nodes stored info related to a user’s account balance and it goes down, he entire banking system will not be able to work.

- Replicating the most important data. This reduces the impact in case one of the nodes containing a subset of high-priority data goes down and also improves harvest.

Another notable observation made in the paper is that while it is possible to replicate all of your data, it doesn’t do a lot to improve your harvest/yield while increases the cost of operation substantially. This is because the internet works based on best-in-effort protocols which can never guarantee 100% harvest/yield.

Application Decomposition and Orthogonal Mechanisms

The second strategy focuses on the benefits of orthogonal system design. It starts out stating that large systems are composed of sub systems which independently cannot tolerate failures but fail in a way that allows the entire system to continue functioning with some impact on utility.

The actual benefit is the ability to provision each subsystem’s state management separately, providing strong consistency or persistent state only for the subsystems that need it, not for the entire application. The savings can be significant if only a few small subsystems require the extra complexity.

The paper states that orthogonal components are completely independent of each other having no run time interface to other components except a configuration interface maybe. This allows each individual component to fail independently minimizing its impact on the overall system.

Composition of orthogonal subsystems shifts the burden of checking for possibly harmful interactions from runtime to compile time, and deployment of orthogonal guard mechanisms improves robustness for the runtime interactions that do occur, by providing improved fault containment.

Over all, the goal of this paper was to motivate research in the field of designing fault-tolerant and highly available large scale systems. Also, to think carefully about the consistency and availability guarantees the application needs to provide and the trade offs it is capable of making in terms of harvest vs yield.