9 minutes

In Search of An Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Raft)

This post summarizes the Raft consensus algorithm presented in the paper In Search of An Understandable Consensus Algorithm by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout. All pull quotes are taken from that paper.

Raft:

Raft is a distributed consensus algorithm. It was designed to be easily understood. It solves the problem of getting multiple servers to agree on a shared state even in the face of failures. The shared status is usually a data structure supported by a replicated log. We need the system to be fully operational as long as a majority of the servers are up.

Raft works by electing a leader in the cluster. The leader is responsible for accepting client requests and managing the replication of the log to other servers. The data flows only in one direction: from leader to other servers.

Raft decomposes consensus into three sub-problems:

- Leader Election: A new leader needs to be elected in case of the failure of an existing one.

- Log replication: The leader needs to keep the logs of all servers in sync with its own through replication.

- Safety: If one of the servers has committed a log entry at a particular index, no other server can apply a different log entry for that index.

Basics:

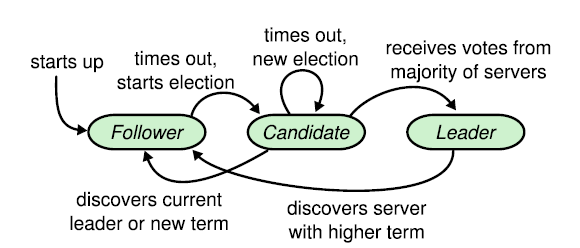

Each server exists in one of the three states: leader, follower, or candidate.

In normal operation there is exactly one leader and all of the other servers are followers. Followers are passive: they issue no requests on their own but simply respond to requests from leaders and candidates. The leader handles all client requests (if a client contacts a follower, the follower redirects it to the leader). The third state, candidate, is used to elect a new leader.

Raft divides time into terms of arbitrary length, each beginning with an election. If a candidate wins the election, it remains the leader for the rest of the term. If the vote is split, then that term ends without a leader.

The term number increases monotonically. Each server stores the current term number which is also exchanged in every communication.

.. if one server’s current term is smaller than the other’s, then it updates its current term to the larger value. If a candidate or leader discovers that its term is out of date, it immediately reverts to follower state. If a server receives a request with a stale term number, it rejects the request.

Raft makes use of two remote procedure calls (RPCs) to carry out its basic operation.

- RequestVotes is used by candidates during elections

- AppendEntries is used by leaders for replicating log entries and also as a heartbeat (a signal to check if a server is up or not — it doesn’t contain any log entries)

Leader election

The leader periodically sends a heartbeat to its followers to maintain authority. A leader election is triggered when a follower times out after waiting for a heartbeat from the leader. This follower transitions to the candidate state and increments its term number. After voting for itself, it issues RequestVotes RPC in parallel to others in the cluster. Three outcomes are possible:

- The candidate receives votes from the majority of the servers and becomes the leader. It then sends a heartbeat message to others in the cluster to establish authority.

- If other candidates receive AppendEntries RPC, they check for the term number. If the term number is greater than their own, they accept the server as the leader and return to follower state. If the term number is smaller, they reject the RPC and still remain a candidate.

- The candidate neither loses nor wins. If more than one server becomes a candidate at the same time, the vote can be split with no clear majority. In this case a new election begins after one of the candidates times out. > Raft uses randomized election timeouts to ensure that split votes are rare and that they are resolved quickly. To prevent split votes in the first place, election timeouts are chosen randomly from a fixed interval (e.g., 150–300ms). This spreads out the servers so that in most cases only a single server will time out; it wins the election and sends heartbeats before any other servers time out. The same mechanism is used to handle split votes. Each candidate restarts its randomized election timeout at the start of an election, and it waits for that timeout to elapse before starting the next election; this reduces the likelihood of another split vote in the new election.

Log Replication:

The client requests are assumed to be write-only for now. Each request consists of a command to be executed ideally by the replicated state machines of all the servers. When a leader gets a client request, it adds it to its own log as a new entry. Each entry in a log:

- Contains the client specified command

- Has an index to identify the position of entry in the log (the index starts from 1)

- Has a term number to logically identify when the entry was written

It needs to replicate the entry to all the follower nodes in order to keep the logs consistent. The leader issues AppendEntries RPCs to all other servers in parallel. The leader retries this until all followers safely replicate the new entry.

When the entry is replicated to a majority of servers by the leader that created it, it is considered committed. All the previous entries, including those created by earlier leaders, are also considered committed. The leader executes the entry once it is committed and returns the result to the client.

The leader maintains the highest index it knows to be committed in its log and sends it out with the AppendEntries RPCs to its followers. Once the followers find out that the entry has been committed, it applies the entry to its state machine in order.

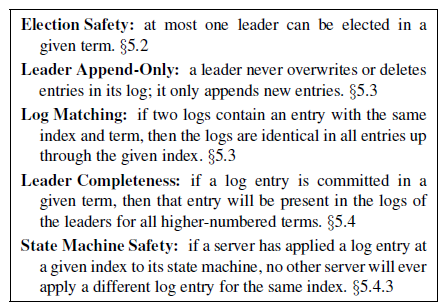

Raft maintains the following properties, which together constitute the Log Matching Property> • If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then they store the same command.> • If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then the logs are identical in all preceding entries.

When sending an AppendEntries RPC, the leader includes the term number and index of the entry that immediately precedes the new entry. If the follower cannot find a match for this entry in its own log, it rejects the request to append the new entry.

This consistency check lets the leader conclude that whenever AppendEntries returns successfully from a follower, they have identical logs until the index included in the RPC.

But the logs of leaders and followers may become inconsistent in the face of leader crashes.

In Raft, the leader handles inconsistencies by forcing the followers’ logs to duplicate its own. This means that conflicting entries in follower logs will be overwritten with entries from the leader’s log.

The leader tries to find the last index where its log matches that of the follower, deletes extra entries if any, and adds the new ones.

The leader maintains a nextIndex for each follower, which is the index of the next log entry the leader will send to that follower. When a leader first comes to power, it initializes all nextIndex values to the index just after the last one in its log.

Whenever AppendRPC returns with a failure for a follower, the leader decrements the nextIndex and issues another AppendEntries RPC. Eventually, nextIndex will reach a value where the logs converge. AppendEntries will succeed when this happens and it can remove extraneous entries (if any) and add new ones from the leaders log (if any). Hence, a successful AppendEntries from a follower guarantees that the leader’s log is consistent with it.

With this mechanism, a leader does not need to take any special actions to restore log consistency when it comes to power. It just begins normal operation, and the logs automatically converge in response to failures of the Append-Entries consistency check. A leader never overwrites or deletes entries in its own log.

Safety:

Raft makes sure that the leader for a term has committed entries from all previous terms in its log. This is needed to ensure that all logs are consistent and the state machines execute the same set of commands.

During a leader election, the RequestVote RPC includes information about the candidate’s log. If the voter finds that its log it more up-to-date that the candidate, it doesn’t vote for it.

Raft determines which of two logs is more up-to-date by comparing the index and term of the last entries in the logs. If the logs have last entries with different terms, then the log with the later term is more up-to-date. If the logs end with the same term, then whichever log is longer is more up-to-date.

Cluster membership:

For the configuration change mechanism to be safe, there must be no point during the transition where it is possible for two leaders to be elected for the same term. Unfortunately, any approach where servers switch directly from the old configuration to the new configuration is unsafe.

Raft uses a two-phase approach for altering cluster membership. First, it switches to an intermediate configuration called joint consensus. Then, once that is committed, it switches over to the new configuration.

The joint consensus allows individual servers to transition between configurations at different times without compromising safety. Furthermore, joint consensus allows the cluster to continue servicing client requests throughout the configuration change.

Joint consensus combines the new and old configurations as follows:

- Log entries are replicated to all servers in both the configurations

- Any server from old or new can become the leader

- Agreement requires separate majorities from both old and new configurations

When a leader receives a configuration change message, it stores and replicates the entry for join consensus C<old, new>. A server always uses the latest configuration in its log to make decisions even if it isn’t committed. When joint consensus is committed, only servers with C<old, new> in their logs can become leaders.

It is now safe for the leader to create a log entry describing C<new> and replicate it to the cluster. Again, this configuration will take effect on each server as soon as it is seen. When the new configuration has been committed under the rules of C<new>, the old configuration is irrelevant and servers not in the new configuration can be shut down.

A fantastic visualization of how Raft works can be found here.

More material such as talks, presentations, related papers and open-source implementations can be found here.

I have dug only into the details of the basic algorithm that make up Raft and the safety guarantees it provides. The paper contains lot more details and it is super approachable as the primary goal of the authors was understandability. I definitely recommend you read it even if you’ve never read any other paper before.