12 minutes

Viewstamped Replication Revisited

This article will distill the contents of the academic paper Viewstamped Replication Revisited by Barbara Liskov and James Cowling. All quotations are taken from that paper.

It presents an updated explanation of Viewstamped Replication, a replication technique that handles failures in which nodes crash. It describes how client requests are handled, how the group reorganizes when a replica fails, and how a failed replica is able to rejoin the group.

Introduction

The Viewstamped Replication protocol, referred to as VR, is used for replicated services that run on many nodes known as replicas. VR uses state machine replication: it maintains state and makes it accessible to the clients consuming that service.

Some features of VR:

- VR is primarily a replication protocol, but it provides consensus too.

- VR doesn’t use any disk I/O — it uses replicated state for persistence.

- VR deals only with crash failures: a node is either functioning or it completely stops.

- VR works in an asynchronous network like the internet where nothing can be concluded about a message that doesn’t arrive. It may be lost, delivered out of order, or delivered many times.

Replica Groups

VR ensures reliability and availability when no more than a threshold of f replicas are faulty. It does this by using replica groups of size 2f + 1; this is the minimal number of replicas in an asynchronous network under the crash failure model.

We can provide a simple proof for the above statement: in a system with f crashed nodes, we need at least the majority of f+1 nodes that can mutually agree to keep the system functioning.

A group of f+1 replicas is often known as a quorum. The protocol needs the quorum intersection property to be true to work correctly. This property states that:

The quorum of replicas that processes a particular step of the protocol must have a non-empty intersection with the group of replicas available to handle the next step, since this way we can ensure that at each next step at least one participant knows what happened in the previous step.

Architecture:

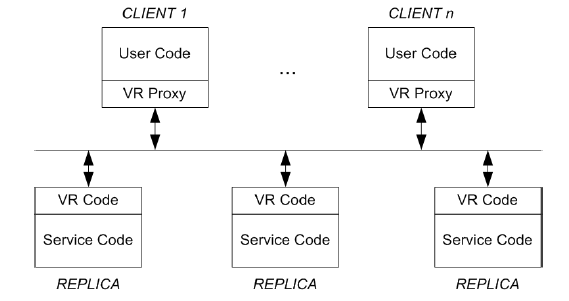

The architecture of VR is as follows:

- The user code is run on client machines on top of a VR proxy.

- The proxy communicates with the replicas to carry out the operations requested by the client. It returns the computed results from the replicas back to the client.

- The VR code on the side of the replicas accepts client requests from the proxy, executes the protocol, and executes the request by making an up-call to the service code.

- The service code returns the result to the VR code which in turn sends a message to the client proxy that requested the operation.

Overview

The challenge for the replication protocol is to ensure that operations execute in the same order at all replicas in spite of concurrent requests from clients and in spite of failures.

If all the replicas should end in the same state, it is important that the above condition is met.

VR deals with the replicas as follows:

Primary : Decides the order in which the operations will be executed

Secondary: Carries out the operations in the same order as selected by the primary

What if the primary fails?

- VR allows different replicas to assume the role of primary if it fails over time.

- The system moves through a series of views. In each view, one replica assumes the role of primary.

- The other replicas watch the primary. If it appears to be faulty, then they carry out a view-change to select a new primary.

We consider the following three scenarios of the VR protocol:

- Normal case processing of user requests

- View changes to select a new primary

- Recovery of a failed replica so that it can rejoin the group

VR protocol

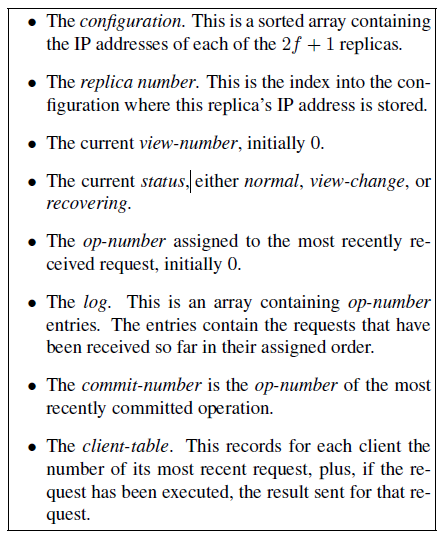

The state maintained by each replica is presented in the figure above. Some points to note:

- The identity of the primary isn’t stored but computed using the view number and the configuration.

- The replica with the smallest IP is replica 1 and so on.

The client side proxy also maintains some state:

- It records the configuration.

- It records the current view number to track the primary.

- It has a client id and an incrementing client request number.

Normal Operation

- Replicas participate in processing of client requests only when their status is normal.

- Each message sent contains the sender’s view number. Replicas process only those requests which have a view number that matches what they know. If the sender replica is ahead, it drops the message. If it’s behind, it performs a state transfer.

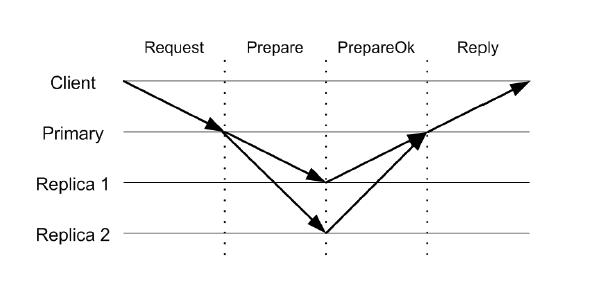

The normal operation of VR can be broken down into the following steps:

- The client sends a REQUEST message to the primary asking it to perform some operation , passing it the client-id and the request number.

- The primary cross-checks the info present in the client table. If the request number is smaller than the one present in the table, it discards it. It re-sends the response if the request was the most recently executed one.

- The primary increases the op-number , appends the request to its log, and updates the client table with the new request number. It sends a PREPARE message to the replicas with the current view-number, the operation-number, the client’s message, and the commit-number (the operation number of the most recently committed operation).

- The replicas won’t accept a message with an op-number until they have all operations preceding it. They use state transfer to catch up if required. Then they add the operation to their log, update the client table, and send a PREPAREOK message to the primary. This message indicates that the operation, including all the preceding ones, has been prepared successfully.

- The primary waits for a response from f replicas before committing the operation. It increments the commit-number . After making sure all operations preceding the current one have been executed, it makes an up-call to the service code to execute the current operation. A REPLY message is sent to the client containing the view-number, request-number, and the result of the up-call.

Usually the PREPARE message is used to inform the backup replicas of the committed operations. It can also do so by sending a COMMIT message.

To execute a request, a backup has to make sure that the operation is present in its log and that all the previous operations have been executed. Then it executes the said operation, increments its commit-number , and updates the client’s entry in the client-table. But it doesn’t send a reply to the client, as the primary has already done that.

If a client doesn’t receive a timely response to a request, it re-sends the request to all replicas. This way if the group has moved to a later view, its message will reach the new primary. Backups ignore client requests; only the primary processes them.

View change operation

Backups monitor the primary: they expect to hear from it regularly. Normally the primary is sending PREPARE messages, but if it is idle (due to no requests) it sends COMMIT messages instead. If a timeout expires without a communication from the primary, the replicas carry out a view change to switch to a new primary.

There is no leader election in this protocol. The primary is selected in a round robin fashion. Each member has a unique IP address. The next primary is the backup replica with the smallest IP that is functioning. Each number in the group is already aware of who is expected to be the next primary.

Every executed operation at the replicas must survive the view change in the order specified when it was executed. The up-call is carried out at the primary only after it receives f PREPAREOK messages. Thus the operation has been recorded in the logs of at least f+1 replicas (the old primary and f replicas).

Therefore the view change protocol obtains information from the logs of at least f + 1 replicas. This is sufficient to ensure that all committed operations will be known, since each must be recorded in at least one of these logs; here we are relying on the quorum intersection property. Operations that had not committed might also survive, but this is not a problem: it is beneficial to have as many operations survive as possible.

- A replica that notices the need for a view change advances its view-number , sets its status to view-change , and sends a START-VIEW-CHANGE message. A replica identifies the need for a view change based on its own timer, or because it receives a START-VIEW-CHANGE or a DO-VIEW-CHANGE from others with a view-number higher than its own.

- When a replica receives f START-VIEW-CHANGE messages for its view-number, it sends a DO-VIEW-CHANGE to the node expected to be the primary. The messages contain the state of the replica: the log, most recent operation-number and commit-number, and the number of the last view in which its status was normal.

- The new primary waits to receive f+1 DO-VIEW-CHANGE messages from the replicas (including itself). Then it updates its state to the most recent based on the info from replicas (see paper for all rules). It sets its number as the view-number in the messages, and changes its status to normal. It informs all other replicas by sending a STARTVIEW message with the most recent state including the new log, commit-number and op-number .

- The primary can now accept client requests. It executes any committed operations and sends the replies to clients.

- When the replicas receive a STARTVIEW message, they update their state based on the message. They send PREPAREOK messages for all uncommitted operations present in their log after the update. They execute these operations to to be in sync with the primary.

To make the view change operation more efficient, the paper describes the following approach:

The protocol described has a small number of steps, but big messages. We can make these messages smaller, but if we do, there is always a chance that more messages will be required. A reasonable way to get good behavior most of the time is for replicas to include a suffix of their log in their DO-VIEW-CHANGE messages. The amount sent can be small since the most likely case is that the new primary is up to date. Therefore sending the latest log entry, or perhaps the latest two entries, should be sufficient. Occasionally, this information won’t be enough; in this case the primary can ask for more information, and it might even need to first use application state to bring itself up to date.

Recovery

When a replica recovers after a crash it cannot participate in request processing and view changes until it has a state at least as recent as when it failed. If it could participate sooner than this, the system can fail.

The replica should not “forget” anything it has already done. One way to ensure this is to persist the state on disk — but this will slow down the whole system. This isn’t necessary in VR because the state is persisted at other replicas. It can be obtained by using a recovery protocol provided that the replicas are failure independent.

When a node comes back up after a crash it sets its status to recovering and carries out the recovery protocol. While a replica’s status is recovering it does not participate in either the request processing protocol or the view change protocol.

The recovery protocol is as follows:

- The recovering replica sends a RECOVERY message to all other replicas with a nonce.

- Only if the replica’s status is normal does it reply to the recovering replica with a RECOVERY-RESPONSE message. This message contains its view number and the nonce it received. If it’s the primary, it also sends its log, op-number, and commit-number.

When the replica has received f+1 RECOVERY-RESPONSE messages, including one from the primary, it updates its state and changes its status to normal. > The protocol uses the nonce to ensure that the recovering replica accepts only RECOVERY-RESPONSE messages that are for this recovery and not an earlier one.

Reconfiguration

Reconfiguration deals with epochs. The epoch represents the group of replicas processing client requests. If the threshold for failures, f, is adjusted, the system can either add or remove replicas and transition to a new epoch. It keeps track of epochs through the epoch-number .

Another status, namely transitioning, is used to signify that a system is moving between epochs.

The approach to handling reconfiguration is as follows. A reconfiguration is triggered by a special client request. This request is run through the normal case protocol by the old group. When the request commits, the system moves to a new epoch, in which responsibility for processing client requests shifts to the new group. However, the new group cannot process client requests until its replicas are up to date: the new replicas must know all operations that committed in the previous epoch. To get up to date they transfer state from the old replicas, which do not shut down until the state transfer is complete.

The VR sub protocols need to be modified to deal with epochs. A replica doesn’t accept messages from an older epoch compared to what it knows, such as those with an older epoch-number. It informs the sender about the new epoch.

During a view-change, the primary cannot accept client requests when the system is transitioning between epochs. It does this by checking if the topmost request in its log is a RECONFIGURATION request. A recovering replica in an older epoch is informed of the epoch if it is part of the new epoch or if it shuts down.

The issue that comes to mind is that the client requests can’t be served while the system is moving to a new epoch.

The old group stops accepting client requests the moment the primary of the old group receives the RECONFIGURATION request; the new group can start processing client requests only when at least f + 1 new replicas have completed state transfer.

This can be dealt with by “warming up” the nodes before reconfiguration happens. The nodes can be brought up-to-date using state transfer while the old group continues to reply to client requests. This reduces the delay caused during reconfiguration.

This paper has presented an improved version of Viewstamped Replication, a protocol used to build replicated systems that are able to tolerate crash failures. The protocol does not require any disk writes as client requests are processed or even during view changes, yet it allows nodes to recover from failures and rejoin the group.

The paper also presents a protocol to allow for reconfigurations that change the members of the replica group, and even the failure threshold. A reconfiguration technique is necessary for the protocol to be deployed in practice since the systems of interest are typically long lived.